بقلم ساندرا ديافيريا، على المدى القصير في OCC اليونان.

Asylum seekers utilise various entry points to reach Greece. Over the past year, the primary entryway into Greek territory has been the Evros River, which forms the border between Greece and Turkey. Additionally, asylum seekers arrive via islands such as Lesvos, the largest island in the eastern Aegean, formerly home to the Moria camp. Chios, situated closer to the Turkish mainland, serves as another significant entry point. Samos is also a crossing point where the ‘new era’ Reception and Identification Centre first began operations, while the island of Kos is another well-known passage for refugees. Once within Greek territory, authorities are obligated to adhere to Article 33 of the Geneva Convention, which mandates respect for individuals seeking asylum in Greece. Unfortunately, in March 2020, Greek authorities shifted their approach, resorting to pushbacks of individuals attempting to reach the Schengen area of the EU without a visa (OCC Greece, 2023), often with the assistance of Frontex.

The asylum procedure includes asylum seekers to request international protection upon their arrival in Greece. After crossing the borders, people on the move are arrested by the Greek police and brought to a police station where they get a paper and then they are transferred to a “Reception and Identification Centres” (RIC) where they are registered. This marks the first official time when they ask for international protection and the asylum card. The RIC centres are situated in the border area of Evros and on five islands: Leros, Lesvos, Kos, Chios, and Rhodos. In some cases, reception camps can also be RIC centres, and this is the case in the islands, and in Diavata and Malakasa. However, unaccompanied minors are excluded from this initial process and they are transferred to specific centres. The asylum procedure commences with the collection of fingerprints, which are then uploaded to the European Central Database (EURODAC) to verify whether the applicant has previously sought asylum in another EU member state. However, in Greece Dublin III regulation is applied mostly in relation to reunification with family members. After registration and fingerprint, asylum seekers receive the Asylum Card. This card is valid for one year and must be renewed thereafter. Upon entering the centre, individuals are typically confined until the completion of their registration. Subsequently, they may be relocated to a Long-Term Accommodation Centre, commonly known as a ‘refugee camp,’ such as Nea Kavala which is one of the 24 long-term accommodation centres on the Greek mainland. However, vulnerable individuals are accommodated in the closest centre to the borders where they had entered Greece (OCC Greece, 2023) (Eleftheria Dodi, OCC Project Coordinator, 2023). Furthermore, asylum seekers typically do not remain in the same refugee camp throughout the entire procedure and this depends on the capacity of these camps. For instance, a former resident volunteer recounted being initially assigned to a camp in Alexandroupolis for 15 days, then transferred to camps in Serres and Thessaloniki before ultimately being relocated to Nea Kavala Camp (former resident volunteer, personal communication, 2023). Similarly, a former student spent one week in Diavata, followed by transfers to Serres, and finally, a stay of approximately 3-4 months in Nea Kavala Camp (former student at OCC, personal communication, 2023).

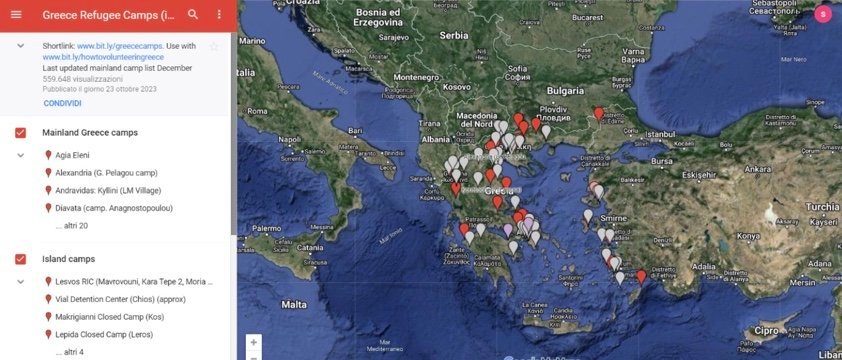

Figure 6: map of Greece Asylum Seekers Camps (Google My Maps, 2022, www.bit.ly/howtovolunteeringreece)

To attain international protection, asylum-seekers must undergo an interview wherein they articulate the circumstances compelling their departure from their country of origin. This interview can be conducted in the RIC or/and camp. Employees of the asylum service go to the camps because the capacity of their offices is too small to host all asylum seekers. However, it still happens that sometimes asylum seekers need to get to the asylum service office (Eleftheria Dodi, OCC Project Coordinator, 2023). In the summer of 2020, the Greek government designated Turkey as a safe third country for nationals of Syria, Afghanistan, Somalia, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. However, many individuals from these countries have been stranded in Turkey for years, often resorting to employment opportunities. Upon arrival in Greece, they are often rejected on the basis of their employment history in Turkey. To counter this, such nationals must prove that Turkey is not safe for them. If the asylum office deems the evidence sufficient, the process proceeds to a second interview (OCC Greece, 2023) . A positive decision grants the asylum seeker either recognised refugee status or beneficiary status of subsidiary protection. Recognised refugee status entitling the individual to a Greek refugee passport. Conversely, subsidiary protection is granted when the individual has no choice other than leaving the country of origin. This status is not recognised under the five categories of the art. 1 of the Geneva Convention, but if the person goes back to his/her country, he/she faces death penalty, persecution, torture, punishment, serious individual threats. Beneficiaries of subsidiary protection are allowed to retain their original passport (if available, otherwise requiring a visit to their embassy in Greece). Individuals granted subsidiary protection may appeal if they believe they are entitled to refugee status. Both recognised refugees and beneficiaries of subsidiary protection receive residence permits, renewable annually for the latter and every three years for the former. However, according to Greek legislation, these statuses can be revoked or not renewed (OCC Greece, 2023) (Eleftheria Dodi, OCC Project Coordinator, 2023).

In the event of a negative decision, the asylum seeker embarks on a lengthy process to challenge it. The initial step involves filing an appeal against the rejection, which is scrutinised by the Appeals Committee. Additional arguments and facts can be submitted to potentially influence a different outcome. Throughout this process, the individual retains the asylum card, and if the decision remains unfavourable, the second step ensues. Within 30 days of the initial appeal, a Petition for Annulment of the Decision must be lodged. The asylum card is taken away and the individual has to go to court. However, before going to court, the lawyer of that person, besides requesting the Petition for Annulment of Decision, has to ask for the suspension for possible deportation. After the decision from the court, in case of a positive outcome, the individual obtains asylum and the resident permit; in case of a negative decision, the applicant has the right to request the continuation of their case examination or submit a new application from the issuance of the suspension decision. This subsequent application must be submitted to the Regional Asylum Office or the Independent Asylum Unit nearest to their place of residence, along with any new evidence that may have emerged. It’s possible that circumstances in the applicant’s home country, previously deemed safe, may have changed—such as the outbreak of war. Following the submission of the subsequent application, the applicant will not receive an international protection applicant card until the Asylum Service approves the request. If the Service rejects the subsequent application, the applicant may appeal to the Appeals Authority within the specified deadline provided in the decision. However, during the review phase of the application, the individual is not shielded from deportation or return (Eleftheria Dodi, OCC Project Coordinator, 2023).

In ‘’refugee camps”, one typically finds individuals seeking asylum in Greece who often aim to relocate to another EU country. However, there are also people who choose not to pursue asylum in Greece and instead opt for irregular border crossings into neighbouring countries. Some individuals, particularly from Afghanistan, Syria, and Pakistan, resort to irregular crossings into North Macedonia due to frequent rejections of their asylum requests in Greece. In the bordering areas, especially near the border checks, numerous irregular routes exist, managed by smugglers who operate within their respective communities. For instance, Syrian smugglers cater exclusively to Syrian nationals, leveraging established diaspora networks within the camps where entire families and communities reside. These smugglers sometimes collaborate with Greek and Macedonian authorities, with reports indicating that authorities near Polykastro push asylum seekers towards North Macedonia. The objective is to traverse Greece swiftly, avoiding fingerprinting and thereby circumventing Greece’s asylum processing procedures, with the ultimate goal of reaching countries like Croatia or Serbia. Individuals seeking to cross Greece covertly often travel from Evros to Thessaloniki before attempting to exit Greek territory. Typically, the trajectory is determined prior to departure from the country of origin, with considerations such as financial factors and the reliability of smugglers playing pivotal roles. In some cases, well-connected smugglers facilitate direct travel from Istanbul to Split in Croatia. Nevertheless, people on the move seldom follow entirely regular routes to their destination countries (Alexis Gkatsis, OCC Greece Coordinator, personal communication, 2023).

“Smugglers can be good friends, and others are very bad, but being an asylum seeker you always end up using smugglers“

(متطوع مقيم سابق، اتصال شخصي، 2023).

What happens after Greece?

Yazidi individuals residing in Nea Kavala Camp awaited asylum approval in Greece before planning their move to another EU country, benefiting from an exemption from the interview process (Alexis Gkatsis, OCC Greece Coordinator, personal communication, 2023). However, this created tension among camp residents, as some obtained asylum quickly based on their nationality, while others had to endure lengthy waits. The Yazidi, persecuted by Daesh, were granted asylum swiftly by the Greek government. I witnessed this firsthand during my time at OCC, as Yazidis and Kurds began migrating to Germany in significant numbers, and new nationalities started participating in OCC activities. Armed with Greek refugee passports, they frequently travelled from Thessaloniki to Germany, leveraging familial ties as crucial resources in accessing employment opportunities. However, one former resident volunteer chose to land in Belgium, where his brother picked him up and they travelled back to Germany together. This decision stemmed from the increasing number of Yazidis facing rejections by German authorities as of November 2023, despite being recognised as refugees in Greece.

Typically, individuals are not permitted to move abroad after receiving international protection in a member state until they obtain citizenship. However, many newcomers opt to forfeit the international protection obtained in Greece and reapply for it in their destination country. Additionally, alternative avenues for legal status in the destination country include family reunification or meeting specific criteria such as employment or enrollment in educational programs, particularly in countries like Germany (Eleftheria Dodi, OCC Project Coordinator, 2023) (former resident volunteer, personal communication, 2023).

During those couple of days at the end of November, short-term volunteers, Yazidis, and Kurdish residents at Nea Kavala Camp experienced similar emotions. The moment of parting is never easy for anyone. In the camp, strangers from the same region come together, forming bonds akin to family as they navigate shared processes and emotions. While newcomers felt a mix of happiness to depart from Greece and sadness to leave their newfound friends behind, they also harboured apprehensions about the future. It was a moment of separation, with hopes of reunification perhaps awaiting them in Germany. Nea Kavala Camp can be viewed as a transient stop along various migratory routes, fostering the convergence of social networks and friendships among its residents. These connections, termed social capital, not only provide crucial pathways for departing migrants but also influence their trajectories to varying degrees as they progress ‘along the way’ (Rumford, 2006; Virilio; Andrijasevic, 2010; de Haas et al., 2020; Schapendonk, 2011).

Does the journey truly end and happiness becomes attainable upon reaching the desired destination country?

“Teacher, I am coming to visit you in your country”

Children harbour hopes of traversing Europe to reunite with their former OCC teachers, while adults yearn to reach their destination countries, reunite with their families, and begin crafting their futures—complete with homes, jobs, relationships, and aspirations to return to assist their communities back home. However, these dreams are often met with disappointment.

Asylum seekers endure prolonged stays in Greece, with some remaining for up to 7 years, especially after their asylum requests are denied. The birth of many babies in transit, witnessed by families in Nea Kavala camps, underscores the enduring nature of their sojourn. Despite being born in Greece, these infants do not acquire EU citizenship but inherit the nationality of their parents through jus sanguinis. Even upon reaching countries like Germany or the Netherlands, newcomers are met with further periods of immobility in camps or reception centres as they await regularisation. This journey, from fleeing their homeland as children to reaching their destination as adults, is an endless odyssey. Upon arrival in Northern Europe, the state of ‘being in transit’ persists, resembling a dystopian narrative that Westerners may struggle to comprehend.

Integration poses another significant challenge, as the stark cultural differences between Greece and Northern Europe can create formidable barriers. Some newcomers, disillusioned by their European experience, yearn to return to their homelands, having discovered over the years that Europe does not align with their interests and aspirations.

المراجع

شابيندونك ج. (2011). مسارات مضطربة للمهاجرين الأفارقة من جنوب الصحراء الكبرى المتجهين شمالاً. جامعة رادبود.